Navarasa literally means, nine emotions.

According to Indian tradition, the basic emotions in life are divided under nine heads; Shringara– love, Hasya– humour, Karuna– pathos, Roudra– anger, Veera– valor, Bhaya– fear, Bhibhatsa– horror, Vismaya– wonder and Shantah– peacefulness.

Each of the following stories is meant to portray one of the Rasas or emotions.

‘Krodha’

Guru Somdeva said, “Of all the emotions, anger is the one which is hardest to hold and maintain for a long time.”

Smoke billowed out from the almost-dead fire, got into Kuppi’s eyes and made them water. She wiped them with the end of her sari and looked up at the crude chimney stuck with broken pieces of bricks. There was a wild wind outside which was blowing in all the smoke, instead of blowing it out. Soon, it would begin to rain, and heavily too, by the look of those dark, menacing clouds.

The wooden plank that served as a door rattled incessantly, even though it had been buttressed by a small tin trunk. Kuppi chopped the spinach mechanically and put the pot of the fire, hoping that Velu would return before the downpour began. Already that morning, he had been complaining of a sore throat, but he had said, “Oh! This will pass off Kuppi, but I just have to go out to our Koundar again this morning and ask him for a few more days – just a couple of days – until I gather some sticks and put up a hut for us. That is the only way,” he had said desperately, “there isn’t any other place and we can’t keep putting him off for ever. After all, it is his own property.”

Kuppi had nodded as she usually did to whatever Velu said, or even anyone else said, for that matter. She had the look of a perpetually startled fawn in her dark eyes, about which Velu would tease her occasionally, “Why, I believe you are even afraid of your own shadow!”

She had nodded and repeated quietly, “Yes, after all, it is his own property.” And had added, as an afterthought, “He is a good man.” Velu had wound a piece of red cloth round his neck and gone out to see the landlord. Then, the rains came.

The fire blazed and smoke alternately as the gusts of wins and rain blew down the chimney. Kuppi tended it as best as she could and went to the door. She opened it a few inches and looked out. Rain burst in through the slit and drenched her hair and face. Velu was turning the corner, his head lowered against the fury of the storm.

Silently, she handed him a cloth to wipe himself with and started swabbing the puddle he was making on the floor. Velu rubbed his hair and began changing his clothes slowly and wearily. “It was no use,” he whispered hoarsely. “Six times I have listened to your excuses’, he said, Kuppi. ‘First it was the harvest season and you were too busy to put up a hut, later on you couldn’t find a suitable place, and then it was one thing of the other. Tell me, isn’t it more than a month now? How long do you expect me to wait? You talk as if you pay me a handsome rent. I helped you out by giving you the place free when you were homeless. Now, when I want it for myself shouldn’t you have the decency to quit?’ he asked. And what could I answer Kuppi? He has been good to us. I could only bow my head and come away, ashamed of myself.”

Kuppi looked at him with the same far-away expression. She took the pot off the fire and served a portion for him. Velu who was used to her, didn’t mind the silence. “No, I don’t want any food. My throat hurts,” he said and lay down on the mat, closing his eyes. After a while, he opened them and said, “He wants us to leave by this evening.”

He slept through the afternoon and evening, breathing heavily at times. Kuppi went about her jobs quietly. Once, when he awoke and asked for water, she touched his arm and murmured to herself, “It is hot.” All night she sat by his side, looking vacantly into space, waiting for the knock which would signal the arrival of the Koundar. When it didn’t come, she was neither surprised nor relieved. The rain continued, unabated.

Velu muttered and groaned and, at intervals, made signs, asking for water. Kuppi poured small sips of warm water down his parched throat. Her gaze flitted fearfully around the small place lit by a tiny wick lamp. “He is ill, terribly ill,” she told herself. Kuppi had never prayed before except to fold her hands automatically in front of the idols at the temple, and she did not begin to do so now. “Whatever will happen, will happen,” she thought. The rain beat down on the roof noisily.

Thursday, the rain turned into a light drizzle and at times the sun shone weakly through the scattered clouds. Kuppi sat in the same place, now and then looking intently at her husband who twisted and moaned with the intensity of the river. It did not occur to her that she had anything else to do but sit beside Velu and watch him. Flies swarmed around the cold fireplace and the uncovered pot of vegetable.

By the evening, the rain had stopped completely. Kuppi hardly noticed that the unnerving drumming overhead had ceased. She rose and opened the door to clear the hot, humid air inside. Shortly afterwards, footsteps sounded and as they approached, an incoherent jumble of voices clarified into sense.

“I told that fellow to clear off last night, but is he still here?” The Kundar sounded worried. “It was raining so heavily yesterday that I didn’t have the heart to throw him out. But, at least today, I expected …..”

“That’s the trouble, master. If you treat these beggars like human beings, they sit upon your head. You should have thrown out their dirty pots and pans on the road – they would have understood, then.”

“It looks as if he is lying down. Perhaps, he is sick.” The Koundar peered through the open doorway doubtfully. There was a short, coarse laugh. “Uh! Sick, my grandmother! You don’t know what tricks these people can get up to. It is just a pretense, he is not more sick than you or I. A hard knock on the head will do him good.”

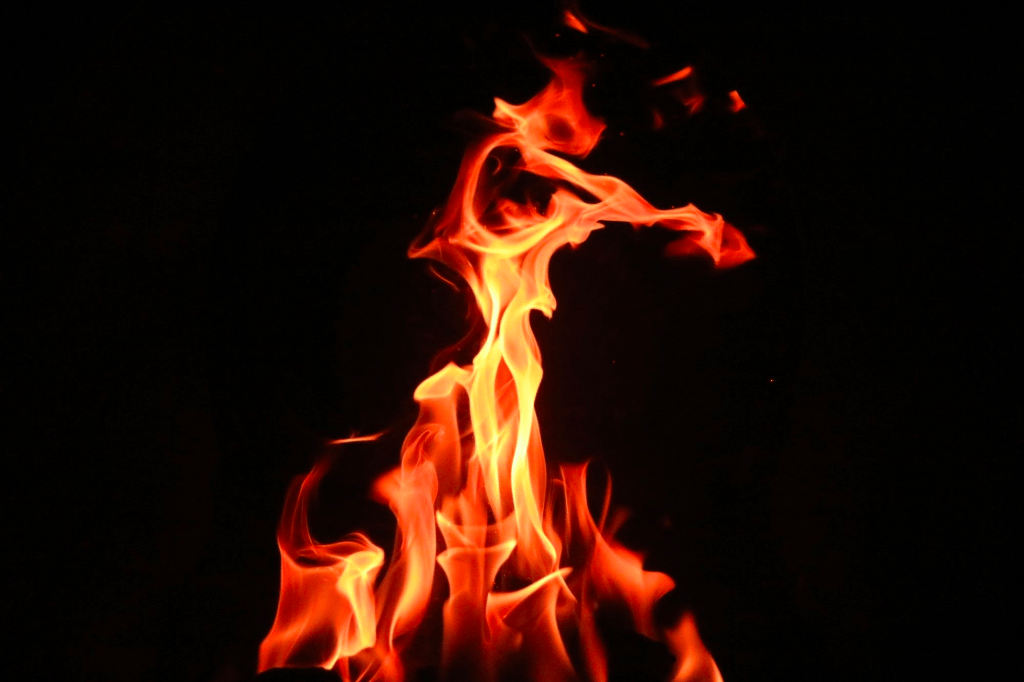

Inside, Kuppi listened, for a time, uncomprehendingly. Then, as the words seeped into her mind, the vacant look suddenly faded from her eyes. They began to blaze.

“And, what if he is sick? Another voice reassured the master. “A little fresh air won’t do him any harm. I suggest the two of us go in, lift him up and put him under the tamarind tree. He won’t die in a hurry, there. What do you say, chaps?”

Kuppi listened. She looked at Velu, lying inert, a huddled form which shivered now and then, and at the menacing group of four at the doorway. A deep primordial rage rose in her. She jumped up, picked up a piece of firewood from the corner and ran to the door.

“Which one said that?” she shouted, as she flailed to right and left with her stick. “Which son of a devil wants to lay hands on my husband? May the curse of heaven fall on you, your father, your grandfather and his father!” she sputtered. Her hair which was in a knot fell loose about her shoulders. “I’ll rip the skin off your backs! Come on, you lion-cubs, let us see what you can do against a woman! Throw him under the tamarind tree, will you?”

In the dying light of dusk, her sleepless, red-rimmed eyes looked wild. She ran up to the Koundar with her stick. “What does it matter if it is your house? Do you have the right to throw him out to die under any old tamarind tree? Tell me, do you have it? How dare you say such a thing?” Her voice rose to a screech and the men fell back hastily.

“This one seems to be snarling like a tigress,” said one of them in wonder. “Shall we leave them be for now?” he asked his master. The Koundar nodded and they returned silently.

For a moment, Kuppi stood watching their retreating backs. Then she looked at the stick in her hand. Once again, her face took on the old, startled expression. She went in, threw the stick back in the corner and sat beside Velu. She felt his forehead. “He is hot,” she thought, “he is ill.” She rested her chin on her hand and watched him, almost absently.