By Sujatha Balasubramanian

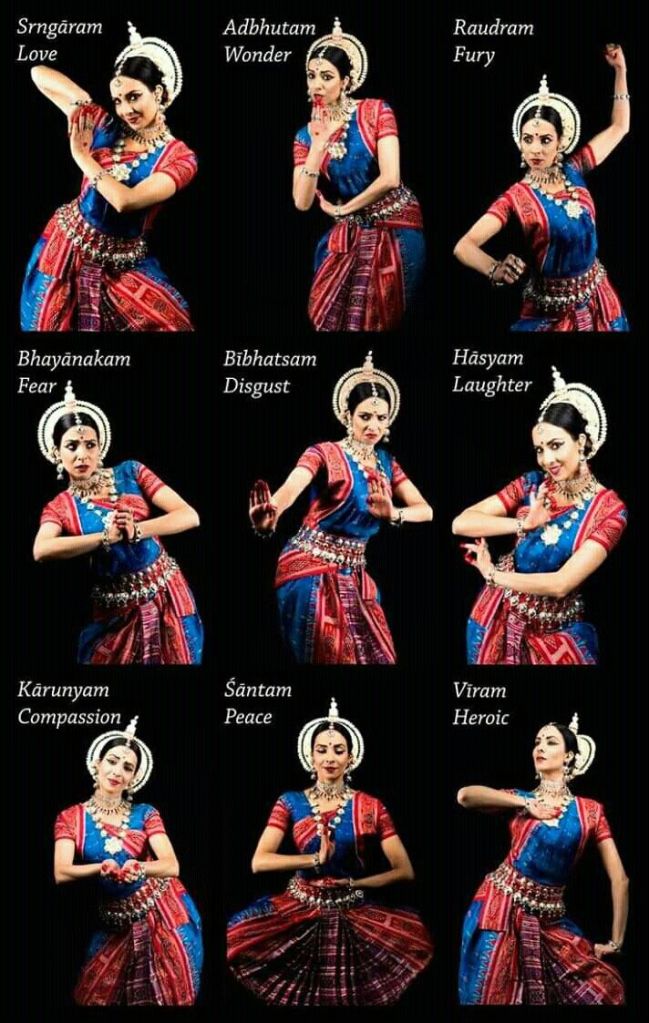

Navarasa literally means, nine emotions.

According to Indian tradition, the basic emotions in life are divided under nine heads; Shringara– love, Hasya– humour, Karuna– pathos, Roudra– anger, Veera– valor, Bhaya– fear, Bhibhatsa– horror, Vismaya– wonder and Shantah– peacefulness.

Each of the following stories is meant to portray one of the Rasas or emotions.

“Thillana, thillana – .” the music flowed into quickening tempo and the drummer beat time with practised ease. Twinkling feet performed with an abandon and a fiery rhythm as if they had a life of their own. The adavus followed one after another, precisely, faultlessly, each a fragment of sculptured beauty.

Mathangi danced with a smile on her face. Behind the smile hid a sulk. I don’t care if he sees it, she thought, though she was careful, very careful not to miss a single beat. That would give him a chance to say: “I told you so.” Sumati, Chitra, Ratna, all of them chosen, and she, the best of them all, still dancing around to the old man’s tune. You are a star among mortals, she mimicked to herself, you shall be a dancer to beat even Urvashi. Oh! The old man knew how to talk, all right, but when it came to doing something – not you my child, he would say, there is still time for you to be presented to the people; have patience. Mathangi executed an intricate pattern effortlessly. The old hypocrite, how I hate him, she thought.

Guru Somdeva wielded a pair of brass bells with slight shudder. What a way to dance, he thought, the ultimate negation of all that he had taught her, the superficial perfection which brought out the slightest flaw with great clarity. That he should have to witness this parody! Have patience, he told himself, contain your anger. She is just a child, mere clay, soft clay in your hands, to be moulded and tempered before she can take any knocks.

The music stopped and Mathangi ended her dance with a graceful bow. No, there was no doubt about it, Mathangi was the best among his students. The poise and charm, dexterity of feet and clarity of line, none of the others could match her in these. But why is it, oh! why is it that there is always something lacking in her? Why can’t one ever find the perfection one seeks for in this world? The paucity is in me, he thought sadly, in my teaching.

“Come here, my child,” he called softly. Mathangi came and sat on the flood beside him. He smiled at her and said, “I know you are angry with me.” Mathangi lowered her head and picked at the loose threads on the mat. She did not contradict him. “It is because I did not arrange for your performance,” the guru stated simply.

Mathangi looked at him with flashing eyes. “All of them, Ratna, Sumati and even stupid Prabha you have sent out,” she stormed. “What is wrong with me? I can dance much better than any of them. Why have you kept me back?”

Guru Somdeva lifted his hand. “Those girls, they are not worth a second thought,” he said, brushing the thought of them aside. “But you, you are different, you are born to something great. Whatever I teach them or however long they dance, they will never be more than ordinary.” He looked at her affectionately. “My Child, you are like a brilliant diamond in my hands. Would you have me leave one of the facets unpolished? Would you have me send you out as anything but flawless? That have one such as you for a pupil has been my prayer and I shall be failing in my duty if I neglect the smallest aspect of your art.”

Mathangi asked softly, “What is wrong? Tell me, what have I missed?”.

He sighed. “You are beautiful,” he said. “Your smile is like a rainbow, spontaneously enchanting. You dance like an Apsara.” He sat up, looking at her sadly. “But that is not all. You are not a mechanical doll, a charming puppet performing certain set of actions. Life is never static or dry. You must live, feel. You must learn how to cry, laugh, rage, fear.” Somdeva rose suddenly, saying, “Look at this. Watch me closely.” He made a sign to the singer and walked across to the centre of the room.

“Nanda nandana, naveneeta chora -.” The words were sung softly over and over again. The guru danced. Mathangi sat on the mat, watching him. Slowly the vision of the sixty-year-old man, still tall and erect, clad in a gold-bordered dhoti, grey hair hanging on to his shoulders, the large dot of sandal-paste gleaming like a third eye in the sensitive face, this familiar vision faded before her eyes. There stood a mischievous, smiling, young boy, now aiming stones at milk-pots, now clambering over his friends to reach the curds, now licking his butter-stained fingers with glee. And then followed an amorous youth dallying with the gopis on the bank of a river. Soon, there was a mortal and terrifying battle with a fierce monster who raged and thundered. Lastly, the scene changed and Mathangi saw a man, greatly perplexed by the mysteries of life and death, and another, calm and serene, who answered and reassured.

Guru Somdeva finished the dance and came over to sit beside her. For a moment, Mathangi was silent, wondering how one man could be all these different people within the flash of an eye. Then, she said slowly, respectfully, “I did not see you, I saw Krishna.”

He leaned forward. “So, you understand? That is what I want of you. You must catch the predominant mood, the bhava and depict it. You should lose yourself and become the one that you want people to see.” Somdeva’s eyes twinkled. “And now, would you like to hear some stories?” he asked containing his weariness. It is worth any trouble, he told himself, if only she can be made to understand the nine rasa bhavas.

Mathangi ascented eagerly, leaning her weight on her left hand, her head tilted to a side in an effort to concentrate. Like any other youngster, she was fond of stories.

Guru Somdeva began.

Very nice.

LikeLike